Click here for the English version.

Um dia antes do meu aniversário de 30 anos, visitei This is Taylor Swift: A Spotify Playlist Experience em Seul, para me despedir da minha juventude. Fui sozinha, encontrei minhas amigas depois, para celebrarmos. Estava usando a pulseira da amizade que ganhei na exposição, e acho que cantamos “You Belong With Me” no karaokê, depois de alguns drinks. No dia seguinte (meu aniversário de fato), acordei em meio a uma terrível crise alérgica. A amiga com quem eu morava na época precisou viajar a trabalho, então passei o dia sozinha, no escuro, abraçada à um rolo de papel higiênico, espirrando sem parar até pegar no sono.

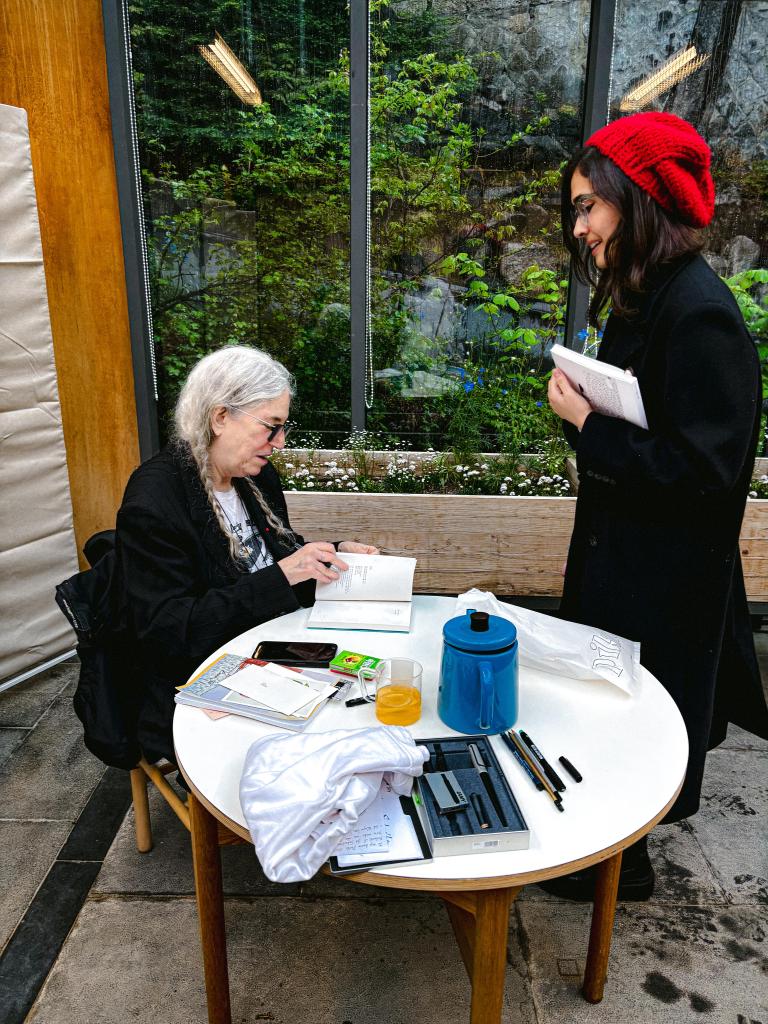

This is Taylor Swift: a Spotify Playlist Experience. Seoul, 1 de Março de 2025.

Depois do meu aniversário, Taylor Swift desapareceu dos meus dias por alguns meses. Não foi de propósito; acho que cansei um pouco da imagem pública dela, mas sempre feliz pela loirinha, sua vida mudando diante dos olhos de todo mundo. A minha também mudava; a trilha sonora dos meus dias juntava vozes novas aos velhos favoritos das minhas piores temporadas, as canções às quais eu recorro quando nada dá certo, o futuro parece um vazio, e a esperança se esconde. Considerando tudo, acho que eu sabia, desde os primeiros teasers, que The Life of a Showgirl não seria a minha praia. De fato, a música não me convenceu, nem me sinto particularmente afeiçoada da narrativa que ela está vendendo. Refletindo sobre esse estranhamento, comecei a pensar nos últimos dois ou três anos da minha vida, na paralisia criativa que se infiltrou pelas rachaduras do meu ofício de escritora, e no meu próprio senso de conexão com a obra e a história da Taylor.

Há quatro anos e meio, eu publiquei um texto chamado “Minhas histórias de amor, contadas por Taylor Swift” — até hoje, o post mais lido do meu site. Na época, deixei bem claro que não me considerava propriamente uma fã; escrevi o ensaio porque achava engraçado que quase todas as minhas histórias de coração partido tinham, de pano de fundo, alguma canção da Taylor. Talvez fosse apenas a estatística jogando a favor das coincidências entre alguém da minha idade e a maior popstar da minha geração. Ainda assim, o verdadeiro motor daquele texto foi que, enfim, eu tinha me conectado com ela, por causa de “invisible string”. A letra tocava o âmago das minhas aspirações íntimas — a inescapável interligação de todas as coisas e a esperança de redenção pelo amor.

Depois disso, fiquei às margens da comunidade de fãs da loirinha, espiando alguns debates de vez em quando, através das Swifties de longa data que conhecia. Acompanhei de perto quando ela lançou Red (Taylor’s Version), mas foi só em Midnights que me senti completamente capturada pelo espírito do momento. Era meu primeiro semestre estudando na Coreia, e eu estava projetando toda a ansiedade de estar sozinha num país distante em um dos poucos amigos que tinha: um artista alto, bonito, interessado em música brasileira. Inspirada pelo álbum, comecei um diário separado, só para os pensamentos que me mantinham acordada à noite — quase todos sobre minha afeição por ele, me questionando se ele sentia o mesmo. Uma semana depois, ele me disse que estava namorando outra pessoa, e logo em seguida começou a me evitar completamente. Uma enxurrada de emoções, antigas e recentes, despencou sobre mim, e eu ainda não tinha raízes profundas o bastante para não me abalar. Eu precisava de ajuda para lembrar quem eu era; “You’re On Your Own, Kid” estava lá, todas as noites, me ajudando a reencontrar meu foco, na caminhada de quinze minutos entre o laboratório e o dormitório.

Ela também estava presente meses depois, quando conheci um cara depois de um jogo de futebol. Ele me acompanhou até em casa, todas as minhas luzes se acenderam; liguei para minha melhor amiga ainda nas escadas, para dizer que tinha acabado de conhecer O Cara Certo. Nosso primeiro encontro foi justamente na época em que ela lançou a edição ‘Til the Dawn de Midnights, com a versão expandida da delicada e etérea “Snow on the Beach”, que acrescentou ainda mais encanto à alegria daquele momento. Taylor, por outro lado, tinha acabado seu relacionamento de seis anos no mês anterior. Foi difícil processar a experiência do sentimento que havia instigado minha conexão com a música dela, mas eu estava tão, tão convencida de que tinha finalmente encontrado o fio dourado da minha invisible string. Imediatamente comecei a planejar uma continuação do meu primeiro texto sobre histórias de amor; antes disso, peguei uma das entradas do meu diário de Midnights e transformei em um texto para celebrar o lançamento de Speak Now (Taylor’s Version), saboreando o prazer de compartilhar algo sobre estar feliz e apaixonada.

Terminamos no fim de agosto, e a ironia não me escapou. Estávamos na Europa, e foi repentino, mas não exatamente uma surpresa — na noite anterior, perto da meia-noite, eu escrevi no meu diário sobre o sentimento de querer ir embora. Mesmo assim, foi brutal; a covardia e a crueldade dele me despedaçaram, abrindo ao mesmo tempo todas as minhas feridas mais profundas. Eu estava longe de casa, cercada de estranhos (que depois viraram amigos), todos gentis o suficiente para me ajudar a manter meus pedaços juntos, até eu poder voltar à Coreia.

Em retrospecto, aquele foi o começo do meu bloqueio criativo.

Quando postei algumas dessas fotos pela primeira vez no Instagram, recebi uma DM dizendo que eu parecia muito leve e feliz. Àquela altura, eu estava há 2, quase 3 semanas sem comer ou dormir, chorando a noite toda e sobrevivendo durante o dia pela graça de Deus e dos meus novos amigos. Linz, Setembro de 2023. Fotos por Patrick Münnich.

Começou com uma enxurrada de palavras, como nunca antes: um parágrafo novo a cada poucas horas, entre as muitas outras tarefas que eu tinha para cumprir. Eu estava desesperadamente tentando criar um caminho lógico para fora do turbilhão do nosso término, mas coisas novas surgiam o tempo todo, nossos caminhos continuavam entrelaçados por amigos e compromissos em comum. Apesar de ter sido um relacionamento tão curto, foi devastador, porque ele abriu um buraco no centro da pessoa que eu acreditava ser. Eu me ressentia por ser quem eu era, e escrevia dia e noite para reorganizar a narrativa da minha vida em algo com que eu pudesse verdadeiramente conviver, para seguir adiante. Paralelamente, eu trabalhava na minha dissertação de mestrado, discutindo sentido e produção de significado, todas as leituras atravessaram a minha crise pessoal e despertaram uma ideia. Queria escrever algo grande, meio científico, meio literário, para processar os detalhes de uma temporada tão intensa e, em última instância, justificar as minhas escolhas de vida — primeiro, diante de mim mesma, depois, diante do meu ex. Eu dormia muito pouco, indo e voltando entre a Coreia e a Áustria, colocando todo o meu tempo livre na busca pela linha de pensamento que me levaria até o magnum opus da minha crise dos vinte-e-tantos.

Desde então, publiquei bastante, correndo atrás dessa visão; criei um blog novo, com uma amiga, e um Substack, para manter as ideias fluindo, mas nada correspondeu às minhas expectativas. Primeiro, eu sentia vergonha de tudo o que escrevia, por toda a humilhação emocional que tinha enfrentado. Também passei a desconfiar dos meus próprios sentimentos e da minha capacidade de dar sentido às minhas experiências, depois de ter me enganado tão gravemente a respeito dele. Emaranhada no drama do nosso rompimento, vivi algumas das oportunidades mais empolgantes da minha vida, mas acabava me autocensurando sempre que tentava articular como me sentia naquele período, como se cada pensamento fosse um terrível lembrete da minha sentimentalidade imbecil. Eu até sentia vergonha de ser escritora, a ousadia de me colocar entre artistas de verdade sem ter nada a oferecer além de um relato vagamente sociológico de sentir e pensar demais. Por fim, eu me sentia cada vez mais sobrecarregada pela escala do que queria fazer. Esse tipo de atitude, eu aprendi, é sinal de que se está tentando compensar em excesso.

Aqueles que nunca superaram a síndrome de underground da adolescência não conseguem entender o que há de significativo em se conectar com uma canção tão famosa que se torna inescapável — ainda mais num cenário midiático tão fragmentado. Eu mesma trabalho com música independente, e minha compositora favorita é uma islandesa obscura, com um cult following (à qual sou devota desde os 17 anos). Mas Taylor Swift é como uma língua comum, uma carta que você sempre pode puxar para se conectar com alguém, até nos círculos mais inesperados. Quando ela lançou The Tortured Poets Department, em meio a tantas críticas públicas, eu a defendi o tempo todo. O número esmagador de músicas foi, para mim, uma grande coletânea de modos de processar as frustrações que eu enfrentava naquele período, de coração partido, e cada vez mais perto dos 30 anos. Não estava conseguindo extrair do momento a escrita que queria, mas tinha as palavras de outros para atravessar os dias.

Mais do que tudo, The Tortured Poets Department soava sincero e desnudo. Havia dor e desalento, visíveis e sensíveis, nos motivos musicais e visuais que ela escolheu para representá-los, mas também confissões lúcidas de atitudes repreensíveis da parte dela. Não é fácil criar algo brilhante, que ainda soe fresco ainda que esteja contando a mesma história que tantos outros já contaram antes. Eu sentia como se estivesse de luto com ela: pelo fim de sua história de amor fatídica, pela perda do “e se” que a acompanhou por uma década, os anos passados em Londres, a vida que ela acreditava que teria. Também havia lampejos de esperança — alguns vindos da carreira, outros do novo relacionamento. Não pude deixar de imaginar que tipo de trabalho teria sido se ela já não tivesse encontrado outra pessoa, antes de lançar o álbum. Se teria sido tão fácil escrever e cantar “I’m pissed off you let me give you all that youth for free” em So Long, London sem um novo amor, algo tão promissor, capaz de suportar o peso de tudo aquilo que ela tinha perdido.

Em vez de postar uma das minhas músicas favoritas de The Tortured Poets Department (a própria title track), vou registrar aqui meu maravilhoso (e inesperado) encontro com a própria Patti Smith. Seoul, 19 de Abril de 2025.

O ponto alto de The Life of a Showgirl é logo a primeira faixa: “The Fate of Ophelia” é simpática e deliciosamente empolgante. Onde a letra sacrifica complexidade emocional em nome da alegoria, a alusão constrói um quadro cativante de redenção — “you saved me from the fate of Ophelia”. Quase como da primeira vez que ouvi “invisible string”, senti um pouco de alívio e esperança — por ela, primeiro, e por mim, em seguida. Há outros momentos interessantes: “Opalite” é divertida e otimista, e “Father Figure” faz muito com raiva e ironia, um clássico instantâneo. A faixa-título, “Life of a Showgirl”, merecia uma resolução mais clara, um pouco menos de clichê (aqui cabe uma menção ao gênio de “Clara Bow”), mas não deixa de ser familiar, o calor da voz de Sabrina Carpenter tornando tudo ainda mais convidativo. O restante soa como uma coleção de rascunhos: ganchos melódicos marcantes desperdiçados em letras duvidosas e frases desajeitadas, as dissonâncias agravadas pelas expectativas que ela cultivou ao longo dos anos. Acima de tudo, não há uma âncora. “Eldest Daughter”, a famosa faixa 5 deste lançamento, foi, francamente, um erro: sem rumo, com letras de mau gosto, uma sátira mal aplicada, a profundidade de um pires.

Eu ia usar este espaço para compartilhar uma excelente video essay sobre o álbum mas decidi que “The Fate of Ophelia” seria mais divertido.

Conteúdo sobre o álbum, na ocasião do lançamento, foi inevitável no meu lado da internet, as reações partindo do bem decepcionante ao completamente frustrante (isso sem contar as demonstrações irracionais de ódio). O volume de discurso em torno de tudo o que Taylor Swift faz é enlouquecedor, mas esse dilúvio de think pieces é justamente o que ela trabalhou para construir — sua carreira foi erguida numa construção coletiva, ajuntando pessoas através do seu jeito de ser extremamente vulnerável, excessivamente detalhada e infinitamente ambiciosa. Mas, para um álbum que pretendia lançar luz sobre o outro lado da fama, Showgirl soa como mais uma performance (e não de propósito). Não acho que o problema seja que ela não tinha o que dizer, como sugeriram alguns, mas não parece que estava pronta para fazê-lo. Talvez o intervalo entre os lançamentos tenha sido curto demais, talvez estivesse exausta da turnê, com uma capacidade de julgamento comprometida (mesmo para um conceito leve). Posso perdoar minha amiga parassocial Taylor Swift por não saber como falar de uma temporada nova e feliz, mas me reservo o direito de sustentar meus critérios, como fã e escritora que espera algo melhor dela.

Ainda assim, parte do seu entendimento próprio parece alinhado ao material; em entrevista a Jimmy Fallon, ela disse que esta é uma de suas eras com a maior correspondência entre como ela se sentia no passado, quando escreveu as músicas, e como se sente agora, ao lançá-las. Lembro de como me senti escutando TTPD, e no significado de olhar para tempos turbulentos a partir da promessa de restituição. Faz sentido que ela soe meio dispersa agora, se estava acostumada a lançar álbuns com mais distância emocional da estação que estava tentando capturar. Talvez parte da dissonância teria sido evitada se a campanha promocional tivesse sido menos pretensiosa, mas as estratégias de marketing também parecem equivocadas, como se ela não percebesse que certas coisas mudaram — até mesmo as expectativas de seus fãs mais fiéis. Esse tipo de miopia, eu aprendi, é sinal de que se está tentando compensar em excesso. Na ânsia de reparar os anos de melancolia, ela falhou em acertar o elemento aspiracional de cantar a própria felicidade. Faltou, nas músicas, algo que me faça querer sair por aí e me apaixonar também.

Em 1:18, ela diz “Essa foi, eu acho, a era mais bem alinhada, em termos de onde minha vida estava, quando escrevi, e onde estou agora, quando foi lançado.”

Refletir sobre a falta de clareza em The Life of a Showgirl me fez pensar na minha crise criativa dos últimos anos, e os motivos pelos quais tem sido difícil escrever sobre uma das temporadas mais intensas da minha vida.

A explicação simples é que nada do que eu escrevi nos últimos dois anos realmente correspondeu à minha visão, nem aos padrões que estabeleci para ela. A parte complicada é como essa visão e esses padrões surgiram. Minhas crises criativas não são de encarar uma página em branco; eu sempre posso escrever algo, dezenas de parágrafos, mas que não resultam em algo que eu queira que outros leiam. Para sair disso, precisava decidir se minha escrita não me satisfazia porque eu precisava trabalhar mais, ou porque eu precisava mudar os parâmetros (“um pouco dos dois” não basta). No fundo, permanecia a esperança de redimir uma temporada tão desastrosa da minha vida através da escrita — dar sentido ao meu estado atual, me convencer de que meu caminho ainda era a vida em que eu acreditava, voltar a me orgulhar daquilo que considerava minha vocação. Eu queria provar alguma coisa, para mim e para os outros, mas a realidade do que eu tinha a oferecer estava em conflito com o que eu queria alcançar. Naquela época, eu não acreditava em mim mesma, nem na vida que tinha escolhido viver. Mesmo agora, ainda não acredito.

O aspecto mais persistente dessa crise é minha desilusão com os limites de histórias e narrativas — uma experiência nova para alguém que sempre se deu bem com os horizontes semânticos da linguagem. De repente, eu passei a odiar a sensação de esmiuçar uma fase difícil até transformá-la numa visão mais otimista, ou de recorrer à interconexão de tudo para encontrar bênçãos escondidas. Minha terapeuta costumava propor que eu aproveitasse a liberdade de interpretar as coisas e dobrar a narrativa ao meu gosto. Em vez disso, eu senti raiva, porque nenhuma mudança de perspectiva a respeito das minhas perdas e fracassos dos últimos anos me dá poder sobre o estado geral da minha vida, nem sobre a liberdade dos outros, de que formem opiniões a meu respeito sem a minha autorização. Controle, controle, controle — a cada rascunho novo, aumentava o desejo de retalhação por cada rejeição e perda dos últimos anos.

Passei a maior parte de 2023 e 2024 ocupadíssima, mas reservei um tempo para essa festa especial do lançamento de 1989 (Taylor’s Version), organizada pelo clube de fãs de Taylor Swift no KAIST. Algumas das minhas amigas não puderam comparecer, então fiz pulseiras da amizade para elas. Meu look foi inspirado em “Welcome to New York.” Daejeon, Outubro de 2023.

As coisas têm sido melhores nos últimos meses, de formas quase milagrosas — do tipo que poderiam me fazer acreditar de novo que ainda estou seguindo o caminho do fio dourado. Escolhi resistir à vontade de agarrar essa sequência de coisas boas e tecer com elas uma imagem falsa de esperança, uma desculpa para expressar o alívio de me sentir um pouco mais no controle da narrativa. Voltar a estar feliz depois de um tempo miserável é um sentimento estranho, cheio de fissuras que exigem atenção total. Nada do que conquistei diminuiu o peso da minha insuficiência, nem me arrancou da sensação de ser inútil e merecer as acusações que me silenciaram. Continuo perdendo o sono com outras coisas, coisas novas. Aqui, preciso sustentar meus parâmetros: nem meus sentimentos nem minha sinceridade significam nada para os outros se não resultarem em algo de substância, fruto do meu trabalho. Enquanto eu estiver escrevendo para me provar alguma coisa, não vou tocar o centro da questão, e não vai ser bom o bastante. O problema está em outro lugar, e eu preciso continuar procurando.

Dos muitos rascunhos e publicações deste período, algumas coisas chegaram, de fato, bem perto do que eu estava procurando. No Corvo Correio, tudo que publiquei desde Setembro de 2023 foi algum tipo de resposta à minha crise criativa (um paradoxo deveras prolixo). Incluindo “loucura e angústia“, sobre a morte da minha avó — algo que escrevi ao longo de um ano, com traços da autoabsorção da ansiedade e dos lados negativos da interconexão de tudo. Meu favorito de todos é “Reduce, Reuse, Recycle: How to be Disposable,” postado originalmente no sappy sallows, durante uma madrugada de estudos. Para aquele blog, eu também escrevi “at a crossroads,” razoavelmente curto, sobre como minhas lutas profissionais, criativas e emocionais estavam interligadas. Por último, “at-a-distance,” a tentativa mais longa, ampla e ambiciosa até agora, de cruzar teoria e experiência, uma bagunça cheia de potencial (com uma menção inesperada à Taylor Swift).

Antes que a seca atingisse o meu Substack, também consegui fazer por lá algumas coisas das quais me orgulho. “Chasing Ideal Types” mostrou como minhas perspectivas filosóficas e sociológicas atravessam minhas experiências, e me ajudou a lidar com algumas rejeições. “Like a Polaroid” capturou diferentes facetas dos motivos pelos quais tenho tido dificuldade para escrever, com mais detalhes e espaço para divagar do que este ensaio atual permite. Em “Nurtured by Ravens,” minha newsletter favorita, compilei trechos de coisas que escrevi sobre meu término, especialmente reflexões sobre a interconexão de tudo, e como ela tanto me abençoou quanto me falhou. Até certo ponto, terminar e publicar esses textos realmente fez com que eu me sentisse mais contente comigo mesma e com o estado da minha vida, ainda que só por um momento.

Eu também experimentei com outros métodos e mídias para expressar minhas ideias e sentimentos. Tanto a Arte quanto as Ciências Sociais me foram úteis neste tempo. Você pode ler mais sobre os projetos nessas imagens aqui.

Minha simpatia sem fim pela Taylor talvez estrague um pouco da minha credibilidade, mas continuo com a impressão de que nós duas estamos trilhando um caminho parecido, ainda que os detalhes das nossas questões sejam completamente diferentes — ela é a maior estrela do mundo, quebrando recordes e se preparando para casar, eu sou a que precisa se preocupar em ter dinheiro para as compras do mês. Mas uma das grandes funções sociais de uma celebridade é se tornar um dispositivo narrativo, um vocabulário público para que pessoas comuns discutam coisas da vida. A mirrorball mais uma vez refletiu minha própria imagem de volta para mim, e eu encontrei algo como resposta. Ao mesmo tempo, por ora, a forma como ela se enxerga no mundo não é a referência que eu quero para mim. Como fã e como escritora, mantenho o meu direito de achar que ela não foi completamente honesta nesse novo lançamento. Mesmo assim, continuo aqui, usando minha pulseira da amizade quase todos os dias, não tanto por ela, mas por todas as outras coisas que ela significa para mim: um lembrete de tudo que fiz para honrar minha juventude, para continuar vivendo com o mesmo coração.

Quanto ao meu bloqueio criativo (ou seja lá como chamar minha crise semântica), acredito que ainda vai demorar até que eu deixe essa temporada no passado. As coisas levarão o tempo que precisam (inclusive este texto, publicado quase duas semanas depois do planejado); eu nunca fui paciente, mas aprendi a ser mais compreensiva. Quanto mais envelheço, mais alguns dos meus problemas parecem ser as perguntas necessárias ao longo do caminho para ser eu mesma. Talvez minhas lutas com sentido e controle nunca desapareçam. Continuo brigando com Deus todos os dias, alimentando a ideia de que talvez eu consiga arrancar alguma soberania de Suas mãos, se me esforçar o bastante. A única esperança para uma controladora é ceder um pouco; se não consigo fazê-lo pela minha paz de espírito, talvez o faça porque preciso alcançar o tipo de honestidade de quem admite a derrota, para lapidar meu ofício e honrar minha vocação. Acreditei que um texto poderia redimir os meus tempos difíceis porque acreditei, acredito, na importância da tarefa de escrever. Mesmo que eu nunca alcance exatamente o magnum opus que imaginei, vou continuar tentando realizar alguma coisa.

Meus agradecimentos à Ashley Chong, minha editora de confiança, e às amigas com as quais eu passei cerca de 200h discutindo esse álbum (e que também tiraram tempo para ler as primeiras versões deste texto): Gésily, Bruna, Gabriela, Rayane, Thaines, Esther, Guilherme, Luiza, e minha irmã Julia.