I visited This is Taylor Swift: a Spotify Playlist Experience by Spotify in Seoul the day before I turned 30. I went alone, to bid my girlhood goodbye, then I met my friends afterwards, to celebrate properly. I was wearing the friendship bracelet I got at the exhibition, and I’m pretty sure we sang “You Belong With Me” at the karaoke. The day after, my actual birthday, I woke up in a terrible allergic crisis. The friend I was living with at the time left for a business trip, and I spent the day alone in the dark, lying next to a roll of toilet paper, sneezing every 45 seconds until I fell asleep.

This is Taylor Swift: a Spotify Playlist Experience. Seoul, 1 March 2025.

That was the last I had of Taylor Swift for a few months. It wasn’t on purpose; though I did get a bit fed up with her public persona, I was mostly happy for her, her life changing before everyone’s eyes. My life was changing as well, the soundtrack of my days mixing fresh voices and old favourites of my lowest times, the kind of stuff you reach towards when nothing works out, the future looks like a void, and hope feels elusive. In this head space, my hindsight bias tells me we knew that The Life of a Showgirl wouldn’t be our cup of tea since the first teasers. I don’t feel convinced by the music, nor am I particularly attached to the narrative she is pushing. Dwelling on this estrangement made me think about the last 2-3 years of my life, the creative paralysis that crept in through the cracks in my duty as a writer, and my sense of connection with Taylor’s work and story.

Four and a half years ago, I published an essay called “My Love Stories, as told by Taylor Swift” — by far, the most popular piece on my website. I made it clear that I didn’t really consider myself a fan of hers around that time; I wrote the essay because it was funny to me that most of my memories of broken hearts had one of her songs playing in the background. Maybe it was just probabilities boosting the overlaps between a person my age, and the biggest pop star of my generation. Nonetheless, the real driving force behind the essay was that I had finally connected with her story, because of “invisible string.” The lyrics spoke to the heart of my intimate aspirations — the inescapable interconnectedness of everything, and the hope of redemption through love.

After that, I settled at the fringes of her fandom, peeking into their conversations from time to time, through the long-term Swifties in my circles. I followed closely when she released Red (Taylor’s Version), but it wasn’t until Midnights that I felt completely captured by the spirit of her time. It was my first semester studying in Korea, and I projected all of my anxiety about being alone in a distant country onto one of my few friends, a tall, good-looking artist with an interest in Brazilian music. Inspired by the album, I started a separate journal just for the thoughts keeping me up at night — mostly about my crush on him, and whether he felt the same. He told me he was dating someone else a week later, and then started avoiding me altogether. A downpour of emotions, present and past, crashed over me, and I lacked the roots to keep me grounded. I needed help to remember who I was; “You’re On Your Own, Kid” was there for me, to help me bring things into focus every night, on the 15-min walk between my lab and my dorm.

She was also there months later, when I met a guy after a football match. He walked me home, all the sparks were flying, I called my best friend as I walked upstairs, to tell her I had just met The One. Our first date was right when she released the ’Til the Dawn edition of Midnights, with an expanded version of the delicate, dreamy “Snow on the Beach,” which added more whimsy to the joy of that moment. Taylor, on the other hand, ended her six-year relationship the month before. I felt quite conflicted about dwelling on the feeling that sparked my connection to her music, but I was so, so convinced I had found the single thread of gold of my invisible string. I planned to write a sequel to my first essay about love stories, once we had been together for long enough; first, I edited one of my midnight journal entries into a text to celebrate the release of Speak Now (Taylor’s Version), and savour the delight of sharing something about being happy and in love.

We broke up by the end of August, and the irony was not lost on me. We were in Europe, and it was sudden, but not a complete surprise — just the night before, around midnight, I wrote a text about feeling that it was time to go. Still, it was brutal; his cowardice and cruelty tore me apart, cutting open all my core wounds at the same time. I was away from home, surrounded by strangers (who became my friends), all of them graceful enough to help me hold my parts together until I could go back to Korea.

In retrospect, that was the seed of my writer’s block.

When I first shared some of these picture on Instagram, someone told me I looked so “genuinely happy.” At that point, I was running on 2-going-on-3 weeks of no food and no sleep, crying through the night and relying on friends to power through the day. Linz, September 2023 (by Patrick Münnich).

It started with writing the most I had ever had, a new paragraph every couple of hours, in between the other things I had to do. I was desperate to rationalise my way out of the maelstrom of our breakup, and new things were constantly coming up, our paths being entangled by common friends and common business. Though it was such a short relationship, it was devastating, because he blew a hole through the centre of the person I thought I was. I resented myself for being me, and I wrote day and night to reorganise the narrative of my life into something I could truly live with, to move on. On the side, as I worked on my Master’s thesis about meaning and sense-making, all the reading I did pierced through my personal crisis, and it sparked an idea. I wanted to write something big, both scientific and literary, to capture the specifics of such an eventful season and, ultimately, justify my life choices — before myself, first, and before my ex, second. I slept very little, going back and forth between Korea and Austria, all of my free time going into looking for the right thought process towards the magnum opus of my quarter life crisis.

I have published a lot since then, chasing my vision; I created a new blog, with my friend, and a Substack, to keep the thoughts flowing, but nothing lived up to my expectations. First, I was embarrassed of everything I wrote, because of all the emotional shaming I endured. I also distrusted my own feelings, and my ability to attach meaning to my experiences, after being so gravely wrong about him. Enmeshed with the drama of our breakup, I experienced some of the most exciting opportunities of my life, but I self-censored whenever I tried to articulate how I felt about that season, as if every thought I produced was an abhorrent reminder of my dumb sentimentality. I was ashamed of being a writer altogether, called out on the audacity of standing in the midst of real artists with nothing to offer but a vaguely sociological account of feeling and thinking too much. Finally, I felt burdened by the scale of what I wanted to do; such a thing, I have learned, is a sign that one might be trying to overcompensate.

Those who never got over their teenage repulse to anything mainstream cannot understand what is meaningful about connecting with a song that is inescapable, more so in such a fragmented media landscape. I work with independent music, my favourite songwriter is an obscure Icelandic woman with a cult following (to which I have been devoted since I was 17). But Taylor Swift is like a common language, a card you can always pull to make a connection, even in the most unexpected circles. When she released The Tortured Poets Department to much public criticism, I was on her side for the most of it. The overwhelming volume of songs was a handy collection of ways to process the frustrations I was dealing with at the time, as I approached my 30th birthday. I couldn’t put together the writing that I wanted, but I had other people’s words to help me through it.

More than anything, The Tortured Poets Department was unmasked. There were pain and dismay, vividly coming through the musical and visual motifs she chose to portray them, but also lucid confessions of reprehensible attitudes on her end. A lot of work goes into crafting something brilliant, that still sounds fresh, even if it’s telling the same story that countless others have told before. I felt like I was grieving with her, the end of her fateful love story, the loss of the decade-long “what-if” in the back of her mind, the years she had spent in London, the life she thought she was going to have. There were also moments of hope — some from her career and work, some from her new relationship. I have sometimes wondered what kind of work it would have been if she hadn’t already found someone else, by the time she released it. If it would have been as easy to write and sing “I’m pissed off you let me give you all that youth for free” in “So Long, London” if there was no promising new lover bearing the weight of all that she had lost.

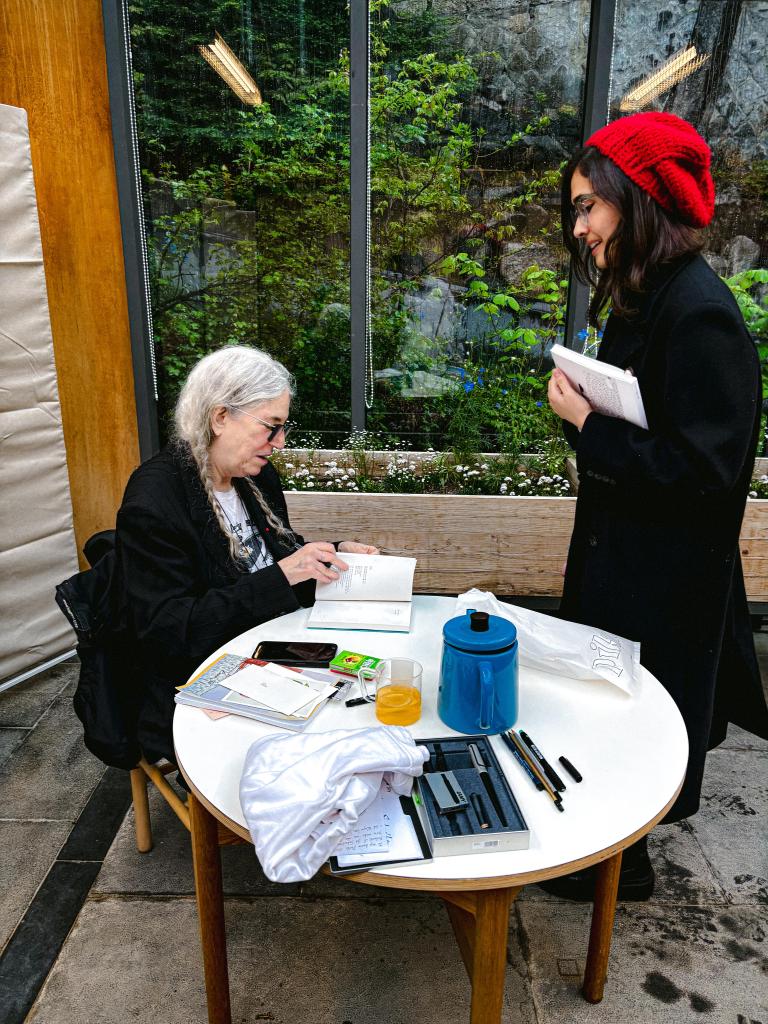

Instead of posting my favourite song from The Tortured Poets Department (the title track itself), I will record here my wonderful, unexpected encounter with Patti Smith earlier this year. Seoul, 19 April 2025.

The highlight of The Life of a Showgirl is the very first song: “The Fate of Ophelia” is likeable and deliciously uplifting. Where the lyrics sacrifice emotional complexity for the sake of the allegory, the allusion paints a touching picture of redemption — “you saved me from the fate of Ophelia.” Like the first time I heard “invisible string,” I felt relieved and hopeful — for her, first, and for myself, second. There are other good moments: “Opalite” is bright and optimistic, and “Father Figure” accomplishes a lot through her rage, an instant classic. The title track, “Life of a Showgirl,” could use a stronger resolution and a bit less cliché (here goes a nod to “Clara Bow”) but it is familiar and inviting, Sabrina Carpenter’s voice making it all the more heart-warming. The rest sounds like a collection of drafts, striking melodic hooks wasted on questionable lyrics with clumsy phrasing, the dissonances aggravated by the expectations she has nurtured over the years. Above all, the whole lacked an anchor. “Eldest Daughter,” the famed track 5 of this release, was, quite frankly, a mistake: no sense of direction, distasteful lyrics with misused satire, the overall depth of a saucer.

I was going to use this space to share a great video essay about the album but then I realised just sharing “The Fate of Ophelia” would be more fun.

Public response to the album has been unavoidable on my side of the internet, ranging from very underwhelmed to utterly disappointed (if we leave out the displays of passionate hate). The volume of discourse surrounding everything Taylor Swift does is maddening, but this deluge of think-pieces is what she worked for — her career was built on bringing everyone onboard her extremely vulnerable, overly detailed, highly ambitious brand of stardom. But, for an album meant to shed light on the other side of her fame, Showgirl sounds like yet another performance (and not on purpose). I don’t think the issue is that she had nothing to say, as some have suggested, but it doesn’t feel like she was ready to do so. Perhaps the time between releases was too short, she was burnt out from the touring, with a clouded judgement (ever for a light-hearted concept). I can excuse my parasocial friend Taylor Swift for being unsure of where she stands during a happy season, but I draw the line as a fan and fellow writer who expects better.

Still, some of her self-awareness seems to align with the material; speaking to Jimmy Fallon, she said this is one of her most well-matched eras, considering where she was when she wrote the songs, and where she is now, upon releasing them. I think back to how I felt about TTPD, and the meaning of her looking back at turbulent times from within the promise of restitution. It makes sense that she sounds all over the place now, if she was used to releasing albums with more emotional distance from the season she was trying to capture. Maybe some of the dissonance would have been avoided if the promo campaign had been less pretentious, but her marketing strategies also seem misguided, as if she can’t tell certain things have changed — even the expectations of her faithful fanbase. Such short-sightedness, I have learned, is a sign that one might be trying to overcompensate; her eagerness to atone for the years of melancholia might have missed the aspirational component of singing about her present happiness. There isn’t much in the music that makes me want to go outside and fall in love as well.

At 1:18, she says “This has just been, like, I think the most well-matched era, in terms of where my life was, when I wrote it, and then where I am now, when it’s out in the world.”

Sifting through the lack of clarity in The Life of a Showgirl made me think of my own writing of the last few years, and the reasons why I have struggled to talk about one of the most eventful seasons of my life.

The simple explanation is that nothing I have written in the last two years or so has truly satisfied my vision, and the standards I set for it. The complicated part is how the vision and the standards came to be. My brand of creative crisis isn’t me staring at a blank page; I could still write paragraphs by the dozens, but they rarely amounted to anything I wanted to let others read. To hope to get out, I had to decide whether my writing was falling short because I needed to work harder, or because I needed to move the benchmark (“a little bit of both” is not enough). Underlying all of it, the hope I entertained, of redeeming such a disastrous season through writing — to make sense of my current state, to convince myself that my path was still the life I believed in, to feel once again proud of what I considered to be my calling. I was eager to prove something, to myself and to others, but the reality of what I had to offer was at odds with what I wanted to accomplish. Back then, I didn’t really believe in myself at all, or in the life I had chosen to live. Right now, I still don’t.

The most enduring aspect has been my disillusionment with the limits of storytelling — an unfamiliar experience, as someone who had always appreciated the semantic horizons of language. I started to hate the feeling of rationalising a difficult season into a more optimistic outlook, or appealing to the interconnectedness of everything to count my blessings. My therapist used to propose that I should relish the freedom to interpret things and bend the narrative to my liking. Instead, I have been angry, because no amount of reframing my losses and failures will grant me power over the overall state of my life, and other people’s freedom to nurture opinions about me that I have not sanctioned. Control, control, control, each new draft increasing my desire of owning up to every failure, rejection and loss of the last few years.

I was busy all the time for the most of 2023 and 2024, but I made the time to attend this special listening party for 1989 (Taylor’s Version), organised by the Taylor Swift club at KAIST. Some of my friends couldn’t come, so I made them all friendship bracelets. My outfit was inspired by “Welcome to New York.” Daejeon, October 2023.

Things have been much better for a couple of months now, in miraculous ways — the kind of thing that could have made me believe once again that I am still tied to the invisible string. I have resisted the urge to grab the streak of good outcomes and weave them into a fake picture of hope, an excuse to express the relief of feeling a bit more in control of the narrative. To feel happy again, after being miserable for a long time, is an unsettling feeling, full of cracks to be watched closely. Nothing I have accomplished has lessened the burden of my insufficiency, or snapped me out of feeling worthless and rightfully shamed into silence. I am still losing sleep over other things, new things. Here, I must uphold my standards: neither my feelings nor my openness mean anything to others unless they achieve something, as a result of my craft. As long as I am writing to convince myself of something, I am not accessing the heart of the matter, and it won’t be good enough. The issue lies somewhere else, and I must keep looking.

Amongst the many drafts and actual publications of this period, a few things did get quite close to the writing I was looking for. On the Raven Post, every single piece posted since September 2023 has been some sort of response to my creative crisis (a paradox, and a very wordy one, if we are being honest). That includes “madness and sorrow“, about my grandma’s death — something I wrote over the course of a year, weaving in traces of the self-absorbedness of anxiety, and the negative sides of the interconnectedness of everything. My absolute favourite one is “Reduce, Reuse, Recycle: How to be Disposable,” originally posted on the sappy sallows. Also for that blog, I wrote “at a crossroads,” a (rather) short account of how my emotional, creative and professional struggles intertwined. Lastly, “at-a-distance,” the longest, broadest and most ambitious attempt I have made so far, of combining theory and experience, messy but full of potential (also, ironically, contains an unexpected mention of Taylor Swift).

Before the drought caught onto my Substack, I did put together a few things of which I am proud. “Chasing Ideal Types” showed how my philosophical and sociological perspectives cut through my experiences, and helped me process a few rejections. “Like a Polaroid” captured different facets of the reasons why I have been struggling to write, with more details and room to wander than this present essay allows. In “Nurtured by Ravens,” my favourite one, I compiled excerpts from things I wrote about my breakup — specifically musings on the interconnectedness of everything, and how it had both blessed me and failed me. To a certain extent, finishing and publishing each of them did make me feel more content with myself and the state of my life, even if for a very short amount of time.

I also experimented with other ways of expressing my ideas, and both Art and the Social Sciences served me a bit during this time. You can read more about the projects in these images here.

My endless sympathy for Taylor Swift might pierce a hole through my credibility, but I am still under the impression that the two of us are walking a similar journey, even though the specifics of our problems are completely different — she is the biggest star in the world, smashing records and preparing to get married, I am the one who has to worry about affording groceries every month. But celebrities are at their best when, to any extent, they serve as a plot device to help common people make sense of their lives. The mirrorball has once again reflected myself back to me, and I was happy to respond. At the same time, for now, the way she sees herself in the world is not the reference I want to entertain. As a fan and fellow writer, I retain the right to think she failed to be completely honest with this new release. I still wear my friendship bracelet everywhere I go, not so much for her, but for the world of other things that it means to me: a reminder of everything I did to honour my girlhood, and to keep living with the same heart.

As for my writer’s block (or whatever we may call my semantic crisis), I believe it will be a while before I put this season behind me. Things will take their time anyway (including this essay, published almost two weeks later than planned); I have never been patient, but I learned to be understanding. The older I get, some of my problems seem to be the necessary questions of being myself. Maybe my struggles with meaning and control won’t ever go away. I am still wrestling with God every day, cradling the thought that I might eventually snatch some sovereignty from His hands, if I try really hard. The only hope for a control freak is to relent a bit; if I cannot do it for my peace of mind, I may do it because I need the type of honesty required to admit defeat, in order to hone my craft, and honour my calling. I believed an essay could redeem the hard times because I believed in the significance of the task of writing. Even if I never accomplish the exact magnum opus I envisioned, I will keep trying to accomplish something.

Many thanks to Ashley Chong, my trusted editor, and to my friends with whom I spent almost 200h going back and forth about this album (and who also took the time to read through the early drafts): Gésily, Bruna, Gabriela, Rayane, Esther, Luiza, and my sister Julia.